Monumental Landscape

Constructing Civic Identity: Commemoration is a key way that Oberlinians have constructed their civic identity and have defined themselves as a distinctive place. Many of Oberlin’s monuments celebrate the outsized role Oberlin played in the fight against slavery. There are memorials to the Oberlin residents who died in the 1859 raid on Harper's Ferry, to those who particpated in the rescue of a fugitive slave, and to the man who organized the first regiment of Black Ohioans in the Civil War. Other monuments highlight Oberlin’s status as a stop on the Underground Railroad and monuments that celebrate Oberlin's abolitionist history continue to be added to the landscape. In 2009, the Toni Morrision Society installed a memorial bench in Oberlin as part of their "Bench by the Road" project Oberlin's bench describes the community as an important stop on the Underground Railroad. Today these monuments don't just commemorate the past, but also serve as a reminder to fight injustice in the present.

Illuminating Changing Values: Monuments can also help us understand how attitudes and values change over time. They can become, in the words of poet Robert Lowell, a “fishbone in the throat” as political values change. The Memorial Arch, erected in 1903 to honor missionaries from Oberlin who were killed in the Boxer Rebellion in China in 1900, is that kind of monument. The huge stone arch, symbolically placed at the entrance to campus, describes the fallen missionaries as martyrs who were doing the important work of spreading Christianity around the world. But by the 1960s, many Oberlin students had come to view missionary work as a form of cultural imperialism. Asian American students protested that the monument was racist. In 1994, students added a plaque to the arch that recognizes the Chinese citizens who were killed during the uprising. Debates over the monument have become less heated since the college decided that graduates would no longer process through the arch in 2010, but the arch remains a contested symbol on campus.

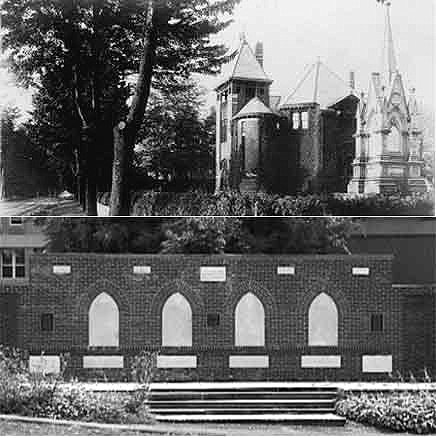

Town and Gown Tensions: Oberlin’s monuments can help track the history of growing tensions between the college and the community. Oberlin’s War Memorial was first erected on college land (at the current site of the Conservatory) as a joint project by the college and the city to honor the 96 Oberlin students and residents killed in the Civil War. But the town and college fought over who should pay to maintain the memorial, and in the 1930s, it became a touchstone for a conflict between Oberlin students opposed to all wars and townspeople who saw military service as a honorable sacrifice. The memorial was eventually moved to public land. When the American Legion updated it in 1983 to include those killed in later wars, they listed only the name of fallen Oberlin townspeople and not those of Oberlin students.

A Reflection of Pride: Memorials can also foster a sense of pride and identity. A small park in Oberlin has become a key site for monuments that honor the city's African American residents. In 1971, The Harper’s Ferry monument was moved from the Westwood Cemetery to site in the southern part of town. That area became Martin Luther King Jr. Park in 1987 whena statue of King was placed there. Since then it has become the home to other monuments that celebrate Oberlin’s African American history, including the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue monument and a monument to the Tuskegee Airmen, the black pilots who fought in segregated air units during World War II. Putting all of these monuments in one place has made this park a space of celebration and pride for Oberlin’s Black community. But does this also represent a kind of segregation of public memory? What does it mean for Oberlin if monuments to racial justice are seen as relating more to the interests of its black residents than its white ones?